Securitisation is the process of issuing securities in which the principal (or capital) and the interest (or coupon) paid are backed by a pool of underlying assets.

Traditional securitisation is a financing technique whereby income-generating assets are typically pooled and sold to a third party (a special vehicle) set up for this purpose. This vehicle then uses these assets as collateral in order to issue securities with varying risk profiles and seniorities (also known as “tranching” of the risk). These securities can then be sold on the financial markets. The underlying assets that can be securitised – and which, individually, may be difficult to trade – can come in various forms, though they are usually loans.

In addition to traditional securitisation, there are other forms in which the credit risk of assets is transferred without actually transferring the assets themselves. Examples include synthetic securitisations and on-balance-sheet securitisations.

How are traditional securitisations carried out?

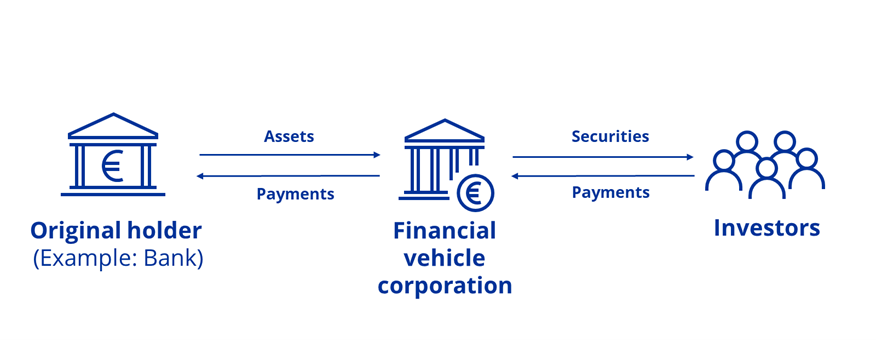

In a traditional securitisation, a pool of assets (usually sharing similar features) is transferred to an entity known as a financial vehicle corporation. The financial vehicle corporation is independent from the original holder of the assets, also referred to as the originator.

The financial vehicle corporation issues securities, usually bonds, which are placed with investors to fund the purchase of the assets. Thus, non-marketable assets are converted into marketable ones.

The return on the bonds is linked to the return on the portfolio transferred, and is isolated from the credit risk of the originator. Different classes of securities can be issued for a given portfolio. Each class has a different level of credit risk, and the returns vary accordingly.

Examples of assets that can be securitised include loans granted by a bank or a specialised lending institution.

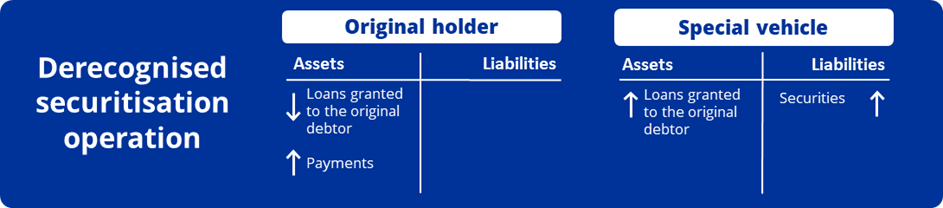

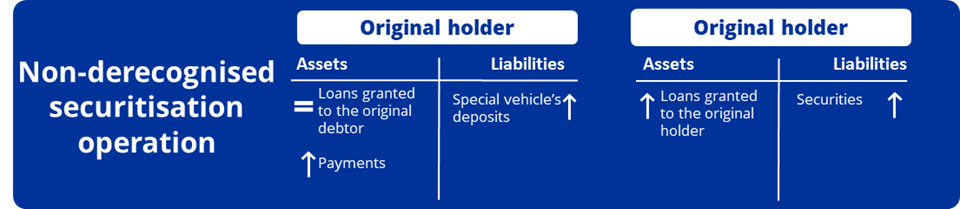

For accounting purposes, traditional securitisation operations can be treated in two ways, depending on whether or not the securitised loans are derecognised (i.e. removed) from the originator’s balance sheet.

What’s the difference between derecognised and non-derecognised securitisation operations?

In a derecognised securitisation operation, the portfolio in question no longer features on the originator’s balance sheet. In non-derecognised operations, the value of the portfolio remains on their books.

From an accounting perspective, when a securitisation operation is derecognised, there is a change in the composition of the originator’s assets: e.g. there is a decrease in loans, alongside an increase arising from the payment received (e.g. in the form of deposits). On the financial vehicle corporation’s balance sheet, meanwhile, there is an increase due to the loans granted to the original debtors (recorded on the assets side), together with an increase due to the securitisation units or securitised bonds issued (recorded on the liabilities side).

When a securitisation operation is not derecognised, the originator’s balance sheet does not vary to the same extent. The securitised loans remain on the bank’s balance sheet. The bank will also record new liabilities arising from the securities issued, together with an increase on the assets side arising from the payment received. On the financial vehicle corporation’s balance sheet, there is an increase in loans granted (recorded on the assets side), as well as an increase in securitisation units or securitised bonds issued (recorded on the liabilities side).

If an original holder is to benefit from a transfer of securitised loans in terms of its capital ratios, it must show its supervisor that it has met the conditions for what is known as a “significant credit risk transfer”. These conditions are distinct from the accounting treatment described above.

Related explainers

What are financial vehicle corporations?